Juliette Alum

Juliette Alum is 18 years old and attends Omoro Secondary School, in Alebtong, Uganda. She hopes to be a teacher one day. Juliette is thankful for her many opportunities, as she realizes that most girls in her culture do not get the chance to attend secondary school. She and many of her classmates stay at […]

Real Stories from one of our Village Savings and Loan Association (VSLA) Programs

While doing our project follow up in Uganda, I was thrilled to see how well our Village Savings and Loan Associations were coming along. We now have 13 groups, which each consist of 30 members. The Village Savings and Loan Association Program or VSLA is a very-structured system of saving, borrowing and lending of money […]

Collin

Collin is a five year old boy from Grand Rapids, Michigan who heard about Drop in the Bucket because of another amazing kid named Ellie. Collin on hearing about everything Ellie is doing to raise money for a well and decided he wanted to help too. Collin decided he would raise money by selling snacks […]

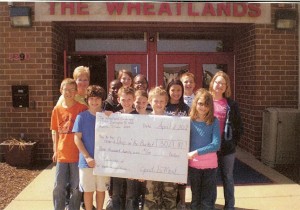

The Wheatlands Elementary School

In February students at the Wheatlands Elementary School in Aurora, IL held an act-of-kindness fundraiser to raise money help build a water well for a school in Africa. Throughout the year the school had been practicing acts of kindness and had made several donations to organizations in their community. This time they decided to take […]

Changing attitudes about female education

The drilling team in South Sudan was starting to make progress, and once we were sure they had reached a place where they could be left to continue, we headed back to Uganda to check on some of our projects there. First stop was Alela Modern Primary School, near Lira, where we had perviously constructed one […]

Charity Atem

Drop in the Bucket has been working at the Alela Modern Primary School since 2009. We drilled at well in 2009 and a year later we went back and built toilets. It was at this school that we met a girl named Charity Atem. Charity was 16 years old at the time of this article. Charity […]

Northern Bahr el Ghazal – the poorest area in South Sudan

Northern Bahr el Ghazal (NBeG) is reported to be the poorest area of South Sudan… and I believe it. The state has a severe lack of infrastructure. Because of the war, and environmental conditions such as regular flooding and droughts, there has been little progress in terms of development. We work closely with many partners […]

When you educate a girl you educate the nation

While having lunch in the South Sudan town of Aweil recently, we had the pleasure of meeting the director for a German NGO, GIZ. He struck up a conversation and when he learned we were helping to provide water in the region, asked if we’d be able to meet with him about something after lunch. Apparently, their […]

Back to the field with travel upgrades

Drop in the Bucket started off the New Year on a great note. We received a wonderful Christmas present this year from UNICEF in South Sudan. They donated two Land Cruisers to assist our field teams in our work. This is a tremendous upgrade for us from old beat down vehicles we’ve been getting around […]

Ellie built a well

6 year old Ellie was shocked to hear that children in Africa did not have clean water, so she went to her school and asked them if they could help her get a well built. With a little help from her Mother, Ellie designed a bracelet that said H2O=Life to sell as a school fundraiser. […]